Making it easier to access the fast-growing Indian market is a challenge.

New Business Age, December 2006

By Madan lamsal & Keshav Gautam

With the existing Nepal-India treaty on trade due to expire in March 2007, debate on whether to renew it for the next seven years or to revise it has started.

The debate started after India proposed to have a Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA) in October covering not only the goods trade, but also investment as well as trade in power and services.

While there would be no problem in having a CEPA, as linking Nepal to fast-growing, easier to access the Indian market is for Nepal ’s benefit, the debate is centred on whether to go for it right away or to leave it till later. The Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FNCCI), the apex chamber of the country, has said that the CEPA proposal should not delay the automatic renewal of the existing treaty. The fear is that such a delay would cause uncertainty as it did when the treaty's renewal was delayed by three months in 2002. FNCCI has suggested continuing the discussion on CEPA without affecting the continuity of the present trade treaty.

But the Confederation of Nepalese Industries (CNI), formed by a group of businessmen who broke away from FNCCI, has demanded for a revision in the existing treaty. In it, they want to incorporate provisions that would effectively address newly emerging trade issues in the region which are gradually liberalising regional trade under the framework of the South Asian Free Trade Agreement (SAFTA) and entering into a cross-regional alliance in the form of BIMST-EC. On this, the FNCCI comment is that any additional provisions that may be agreed upon between the two governments can be incorporated as protocol to the existing treaty whenever such an agreement is reached.

Kush Kumar Joshi, the second Vice-President of FNCCI says, under the present fluid political situation, by trying to tweak the existing treaty, Nepal may lose some benefits that it already has. Badri Ojha, Executive Chairman of Sanima Development Bank views that putting investment as well as trade in power and services in the same treaty may also create problems in implementation.

Despite this debate, both associations agree that several provisions in the existing treaty need to be revised while many others need to be properly implemented. More importantly, as CNI's Vice-President JP Agrawal says, Nepal should break the tradition of simply being the taker of concessions from India .

"Now the treaty between the two countries should be on the basis of equality with both sides giving and taking something in exchange. Nepal should shun the feeling of being the small country which always looks towards favours from India ," he says.

Quoting the bilateral trade data between Nepal and India , he says India 's exports to Nepal are not limited to what is reflected in the official figures. Almost an equal volume as shown as formal imports is coming to Nepal through informal channels. Nepal 's trade deficit with India is over Rs. 65 billion per year as per the latest data estimates. "This means, Nepal is not a small market for India . But we have not been able to make India realise this," he adds. Though Agrawal's estimates for informal trade is a bit higher, a recent study by Readers Dr. Puspa Kandel and Dr. Rajendra Shrestha has estimated informal imports at about 40 per cent of the total formal trade and there is no doubt that India too is benefiting a lot. As per the study by Kandel and Shrestha, it is estimated that Nepal suffered an informal trade deficit of over 7 per cent of Nepal 's Gross Domestic Product.

Meanwhile, indications are that India will not like to go for a full-fledged Free Trade Agreement (FTA) with Nepal or, for that matter, with any of its neighbours. The existing FTA with Sri Lanka has been already revised by fixing quotas on items like vegetable ghee which were allowed into India from Sri Lanka without any restrictions until recently. A study by the World Bank has recently advised India not to go for FTA with Bangladesh either. Rather, it has suggested to further liberalise bilateral trade with Bangladesh . The same idea seems to be behind the CEPA proposed with Nepal. But some analysts have also guessed that the proposed CEPA is similar to the one India signed with Singapore recently.

Existing problems

As the details of the Indian proposal for the CEPA are not made public, Nepali authorities seem to still be in a dilemma about it while the time for the decision-making is passing by quickly as the renewal date for the existing treaty is pretty close. However, the Nepali business community is still full of complaints regarding the non-compliance of the provisions of the existing treaty. In such a situation, it is difficult to see the benefits, if any, in the proposed changes.

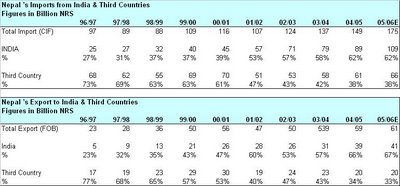

The trade treaty signed between Nepal and India in 1996 is hailed as a milestone in Indo-Nepal trade relations but the revisions made in 2002 have proved to be restrictive. For example, in 1996/97, only 26 per cent of the total imports of Nepal was from India . That increased to 57 per cent in 2002/03. During that period, the share of India in Nepal's total imports grew from a mere 23 per cent to 57 per cent while India's share in Nepal's total exports grew from 23 per cent to 53 per cent.

But the 2002 revision in the treaty that imposed a quota restriction on major items of Nepal 's exports, decelerated this trend. The share of India in total exports and imports in Nepal increased marginally to 67 per cent and 62 per cent only in 2005/06.

The problems, however, do not lie simply on the quota restrictions. The problems that the Nepali business community is raising repeatedly can be grouped under headings like non-tariff barriers, bureaucratic hassles and tariff issues.

The issues

Various state governments of India have been imposing sales tax and luxury tax on goods imported from Nepal. The Nepali business community says this is against the basic spirit of the trade treaty. The treaty is based on the principle of not discriminating against the Nepali goods that are imported into India by fulfilling the requirements specified in the treaty.

The other issue is related to the relief to the products of Nepali small scale units imported into India. Clause number (3) under article V of the treaty protocol has provided for relief in excise duty on products produced by small-scale Nepali industries. The Nepali business community says this provision has not been implemented at all till now.

The most frequently raised issue is the one related to quarantine. While the number of quarantine check posts in India along the Nepal-India border is not sufficient, the service charge levied on testing agricultural products is very high. More importantly, India has not allowed partial shipment of less than 100 MT for quarantine purposes. These restrictions have posed hurdles in the development of such businesses as seed production and plant nurseries are the core areas of competency of Nepal.

Similar to quarantine is the problem of laboratory to test drugs and cosmetics. Raxaul is the only entry point specified for drugs and cosmetic exports from Nepal to India. But as Raxaul has no testing facility, the samples have to go to Kolkata for the tests. Though the Indian government has promised to open a testing facility at Raxaul, the matter has been pending for a long time. Till the Raxaul facility is set up, the Nepali business community suggests that the previous practice of allowing well-known brands of drugs and cosmetics from Nepal to India without the laboratory test should be reintroduced.

Another problem is again related to the quality or standard concern of India regarding imported products. Indian authorities require the products entering India to meet the standard fixed by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). Though there have been several meetings between the authorities of both countries to recognise the standard of the Nepal Bureau of Standard and Metrology (NBSM) to be equivalent to the BIS standard, this is still not finalised. The Nepali business community has suggested that both parties follow the previous rule as long as this issue of equivalency of NSBM and BIS standard is not finalised.

The quota restriction is understandably the other major issue about which the Nepali business community is complaining. But the complaint is not simply on the quota. Instead, it is on the rationality of the blanket quota restriction.

For example, the quota fixed for copper products is applicable also on copper handicraft items even if India has no problems of import surges in such items. The Nepali business community suggests that the quota restriction should be applicable only on items in which India faces surges in imports. As it may be recalled, India has claimed a surge in bare copper wire only, while the quota restriction has covered all products of copper and copper alloys.

Another point raised by the Nepali business community is more specific about the spirit of the treaty which is to provide a level playing field to Nepali products in India . While the Nepali manufacturing units import raw material form India , they have to pay excise duty on them in India . When the products from Nepal (including those made by using the Indian raw materials) are exported to India , countervailing duty (CVD) is to be paid on them and this duty is levied on the maximum retail price of the products. This has made the Nepali products uncompetitive in India . Nepali exporters claim that the Nepali exports would have been Rs. 3 billion higher per year than what they are now if these problems didn't exist. Their demand is to waive excise on raw materials exported to Nepal and to levy the Indian CVD on Nepal 's exports to India only on the transaction value.

Predictability Concern

As can be evident, the points raised by the Nepali business community are related with the concerns of predictability of access to the Indian market. The basic reason undermining the predictability is not so much on the treaty's provisions as it is on the Indian bureaucracy which in turn is caused by the fact that the trade between Nepal and India is through land routes. The unpredictable behaviour of Indian customs and excise authorities and state governments who change the rule and practice frequently is causing unnecessary additional costs to Nepali exporters.

The Nepali business community even claims that the Indian excise authorities are not sufficiently aware about the procedure of export to Nepal (hence the archaic excise rules on exports to Nepal , particularly of raw material). As this has been discouraging the Indian exports to Nepal, the Nepali trade negotiators would do better by trying to do solid homework on this and convince the Indian negotiators how this system is discouraging Indian exports.

In exports to India , the problem with the Indian excise administration, as pointed out specifically by the Nepali business community, is related to the excise administration of Bihar and UP. They have been frequently detaining consignments from Nepal citing different excise rules whereas these rules are not applicable in case of goods imported in India from Nepal with valid certificates of origin issued in compliance with the provisions of the Indo-Nepal trade treaty. Another problem related with the certificate of origin is due to the file appraisal system practiced in Indian Customs. Nepali business community says the file appraisal is quite redundant as it is already replaced by the provision of certificate of origin made in the Indo-Nepal trade treaty.

Another instance of archaic interpretation of the rules by the Indian bureaucracy is provided by the cases under goods imported through Letters of Credit (L/C). Indian Customs officers insist that the goods being exported to Nepal should arrive at the Customs point by the date of shipment mentioned in the L/C. This is an archaic interpretation as anyone can see that the shipment date mentioned in L/C is the date when the goods have to be dispatched from the premises of the exporter (or at best the date when the transporter issues the date of receiving the consignment for dispatch).

The Nepali business community has also demanded a system to quickly redress the trade disputes when they arise between Nepali and Indian parties. Also demanded is a system through which the holidays in the Indian Customs coincide with holidays at the Nepali Customs. At present the Indian Customs are closed on Sundays for weekly holidays whereas in Nepal they are closed on Saturdays. Because of this, 50 days of business are lost in a year. But why this problem has not been resolved is still a mystery because it can be solved by the Nepali government itself because it can easily order the Nepali Customs offices along the India border to observe weekly holidays on Sundays instead of on Saturdays.

India 's concern

India 's main concern in trade with Nepal is the possibility of trade deflection, i.e. possibility of third country goods being re-exported to India . Hence the frequent changes in the rules and the excessive discretionary powers vested on the Customs and excise authorities of India . And this was the main concern even in 1970s. Obviously, the maze of myriad rules and discretionary powers vested in Customs and excise officers have not proved as effective as desired. Also, Indian government authorities are more likely to listen to the points of the Nepali exporters if the Nepali trade negotiation team puts these points across logically. India's proposal to have a CEPA should be taken as an opportunity in this regard as it allows the review of the gamut of Indo-Nepal trade and economic relations, not only on the micro issues, as noted above.

But there are two internal hurdles within Nepal . First, Nepal lacks a competent body for international trade negotiations. The Ministry of Industry, Commerce and Supplies (MOICS) and the Department of Commerce, manned by frequently transferred government employees, cannot have such competency. Second, a point which is closely related with the first, is the likely dillydallying till March in doing the necessary homework. This is more probable because the Nepali government bureaucracy has a tradition of going by fire brigade style of management (or management by creating crisis) and this has not changed even after Janaandolan-2. Third, as the political situation is still in the transitional stage, pressures from different vested interest groups (both from industry and commerce as well as political sectors) are likely to make it difficult for the Nepali trade negotiators to take a pragmatic approach while negotiating with India . Perhaps this is on the mind of Purushottam Ojha, whom the government has reappointed as the Joint Secretary of MOICS after moving him around other ministries for some years. When he was addressing a discussion organised recently by South Asia Watch on Trade, Economics and Environment (SAWTEE), Ojha remarked that Nepal should be careful when negotiating for the treaty's revision, otherwise there is risk that even some of those benefits that are already there may be lost.

Nepal's Trade with India and Third Countries

If this is the case, it may be wiser to go for automatic renewal, rather than revision. However, this will definitely delay the pace of the progress Nepal could make by opening new opportunities in revising the treaty to suit present times. But the heavy influence of leftist parties in the present government is likely to make it difficult as they strongly believe in the Dependency Theory and take India as the force that always wants to keep Nepal dependent. Perhaps Indian authorities understand this and they have indicated they will be more accommodative with Nepal now. The latest indication came from the Indian Foreign Minister Pranab Mukherjee while on his one-day Nepal visit on December 17 when he said India was ready to discuss reviewing even the 1950 Peace and Friendship Treaty between Nepal and India. All the left parties have repeatedly demanded the review or even abrogation this treaty.

No comments:

Post a Comment